80% Of The Times, Scaling Is Not a Rewrite Problem

How a single interview question reveals who understands load, risk, and trade-offs

This question looks simple. It isn’t.

You inherit a production monolith that starts failing during peak traffic. You have 90 days to improve scalability. A full rewrite is not an option. What do you do?

This is one of the best system design interview questions I’ve heard.

Not because it tests tools. Not because it tests architecture diagrams.

But because it tests something much harder:

Can you reason under real constraints?

Most candidates hear this question and immediately say:

“I’d break it into microservices.”

That answer usually fails.

Not because microservices are bad. But because rewriting a system that’s already failing is the fastest way to make things worse.

This question is really about judgment.

And judgment is the core skill that System Design interviews aim to measure.

If you want to train this kind of judgment intentionally, this is exactly what we focus on at joinenginuity.com.

Not memorizing architectures, but learning how to reason under constraints, pressure, and incomplete information.

To make it easier to get started, here is a 30% off for the first 25 engineers using the coupon code ENGCLASSROOM30.

Before jumping into timelines and tactics, there is a step many candidates skip entirely.

It is the most important one.

If you do not get this right, every decision that follows will be flawed, even if your architecture skills are strong.

First: Reframe the problem

Before timelines, phases, or technical steps, this question tests something more basic: can you restate the problem correctly?

Most system design failures don’t start with bad code. They start with a bad understanding of the problem being solved.

So before touching architecture, you need to show that you understand what actually matters in this situation.

Before touching code or architecture, I restate the problem in system terms.

What we actually know:

The system is already in production

It fails under peak load, not average load

Revenue depends on it

You have 12 weeks, not a year

A full rewrite is explicitly disallowed

That changes the goal.

Now the goal is not elegance; focus on stability under peak pressure.

Increase peak capacity, reduce blast radius, and buy time.

If a candidate doesn’t say this out loud, they usually miss the intent of the question.

Up to this point, everything has been about thinking clearly.

Now it is time to act.

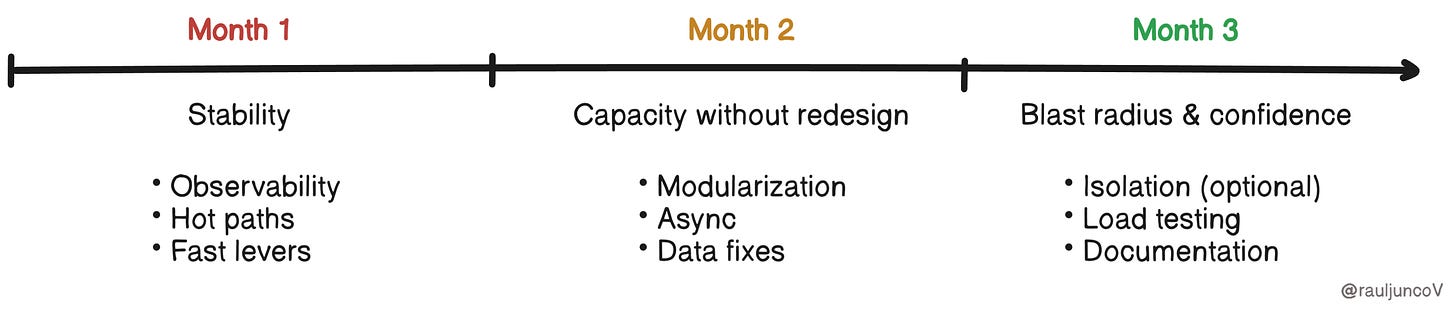

The first phase is not about scaling up. It is about preventing things from getting worse, and it should take roughly two to four weeks.

Month 1: Stop the bleeding

This phase is about survival. Before you can start to think about scale, elegance, or future architecture, you need the system to stay up long enough to learn from it.

1. Add observability before changing behavior

If the system is failing and you don’t know why, every change is a guess.

So the first move is visibility:

Request latency (p50 / p95 / p99)

Error rates by endpoint

Database query timing

Connection pool saturation

CPU and memory pressure

If tracing is missing, add basic tracing.

Why this matters:

Scaling without observability is like load testing blindfolded. You might change something, but it’s impossible to know if it helped.

2. Identify the hot path

Under peak load, not everything matters.

Usually it’s:

Checkout

Inventory reads

Pricing

Auth/session validation

I look for:

N+1 queries

Synchronous downstream calls

Unbounded fan‑out

Lock contention

Chatty ORM behavior

System design is about leverage.

Fix the path every request touches. Ignore the rest for now.

3. Pull fast, reversible levers

No refactors yet. No rewrites.

Only changes I can roll back quickly.

Typical examples:

Add read replicas

Introduce cache‑aside for hot reads

Add timeouts and circuit breakers

Rate‑limit non‑critical endpoints

Tune connection pools carefully

In parallel, I apply infra‑level scaling levers that are cheap and reversible:

This includes tuning instance sizes, autoscaling policies, container CPU and memory limits, and thread or connection pool sizes. These changes often buy immediate headroom and reduce cascading failures before any deeper work begins.

The goal of Month 1 is simple:

Survive the next peak.

Month 2: Increase capacity without redesign

Once the system stops falling over, the goal shifts. Now, you increase throughput and reduce pressure, without introducing risky structural changes you can’t easily undo.

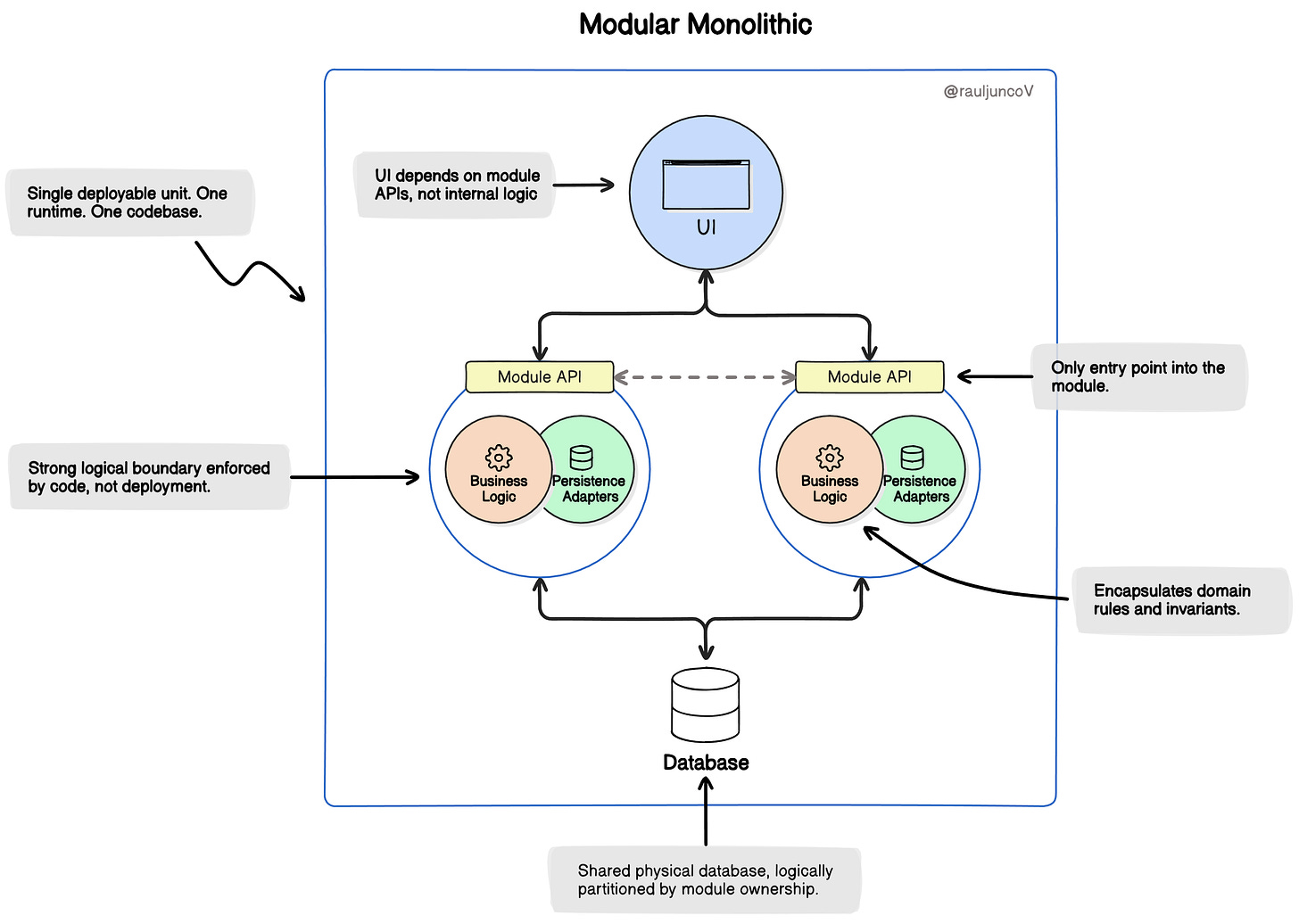

4. Turn the monolith into a modular monolith

This is where strong candidates separate themselves.

They don’t jump to the network. They start with boundaries.

Actions:

Split code by domain, not layers

Introduce explicit interfaces

Remove shared global state

Make dependencies visible

This reduces:

Change risk

Accidental coupling

Debug time

A modular monolith scales better than a distributed system built in panic.

5. Move expensive work off the request path

Peak traffic dies in synchronous work.

Common offenders:

Email sending

Payment callbacks

Inventory recalculation

Analytics writes

Fix:

Convert sync → async

Push work to background workers

Return

202 Acceptedwhen possible

Rule of thumb:

If it doesn’t need to block the user, it shouldn’t block the request.

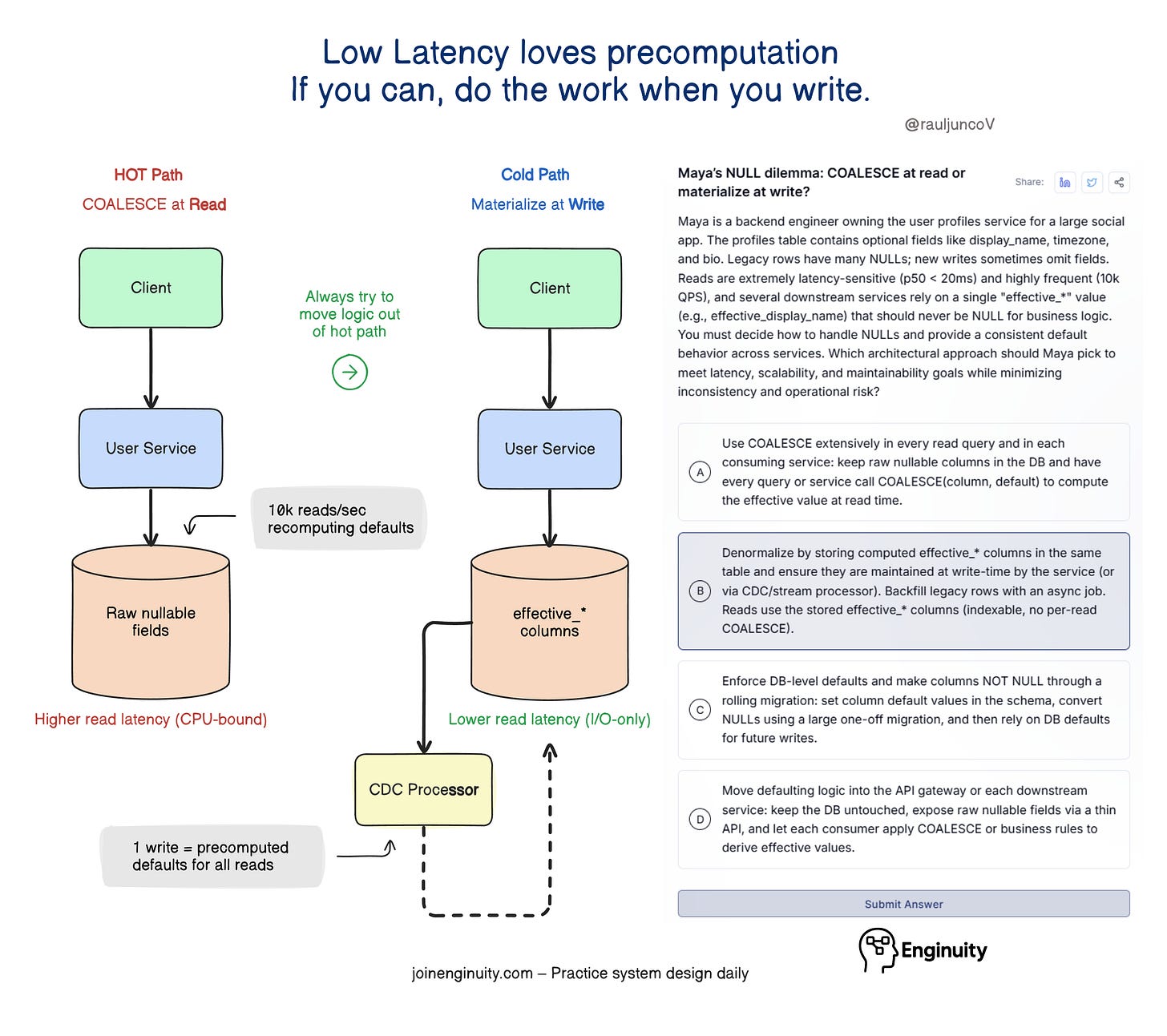

6. Apply targeted data fixes

Most scalability problems show up in the database first.

I focus on real queries and real traffic patterns, not theoretical models. Missing indexes, unnecessary transactions, and overly strict isolation levels are common causes of peak‑load failures.

I focus on real queries, not theory.

Typical wins:

Add missing indexes

Remove unnecessary transactions

Lower isolation levels where safe

Precompute reports instead of running them live

Cache computed aggregates

When caching is introduced or expanded at this stage, it must be done carefully.

Caching pitfalls matter:

Cache stampedes can take systems down faster than databases. I look for basic protections such as request coalescing or locking, jittered TTLs to avoid synchronized expirations, and clear rules around invalidation. I also make explicit decisions about where stale reads are acceptable and where they are dangerous, especially around pricing, inventory, and payments.

Caching should reduce pressure, not introduce a new failure mode.

No heroic schema redesigns. Only changes justified by metrics.

Month 3: Reduce blast radius and create options

At this point, the system should be stable under peak load. Month 3 is about turning that stability into confidence and making future failures smaller, slower, and easier to manage.

7. Isolate the biggest offender (optional)

If one domain dominates load and boundaries are clean:

Extract one worker or service

Keep the contract small

Avoid creating new coupling

This step is optional.

Many systems stabilize without any extraction at all.

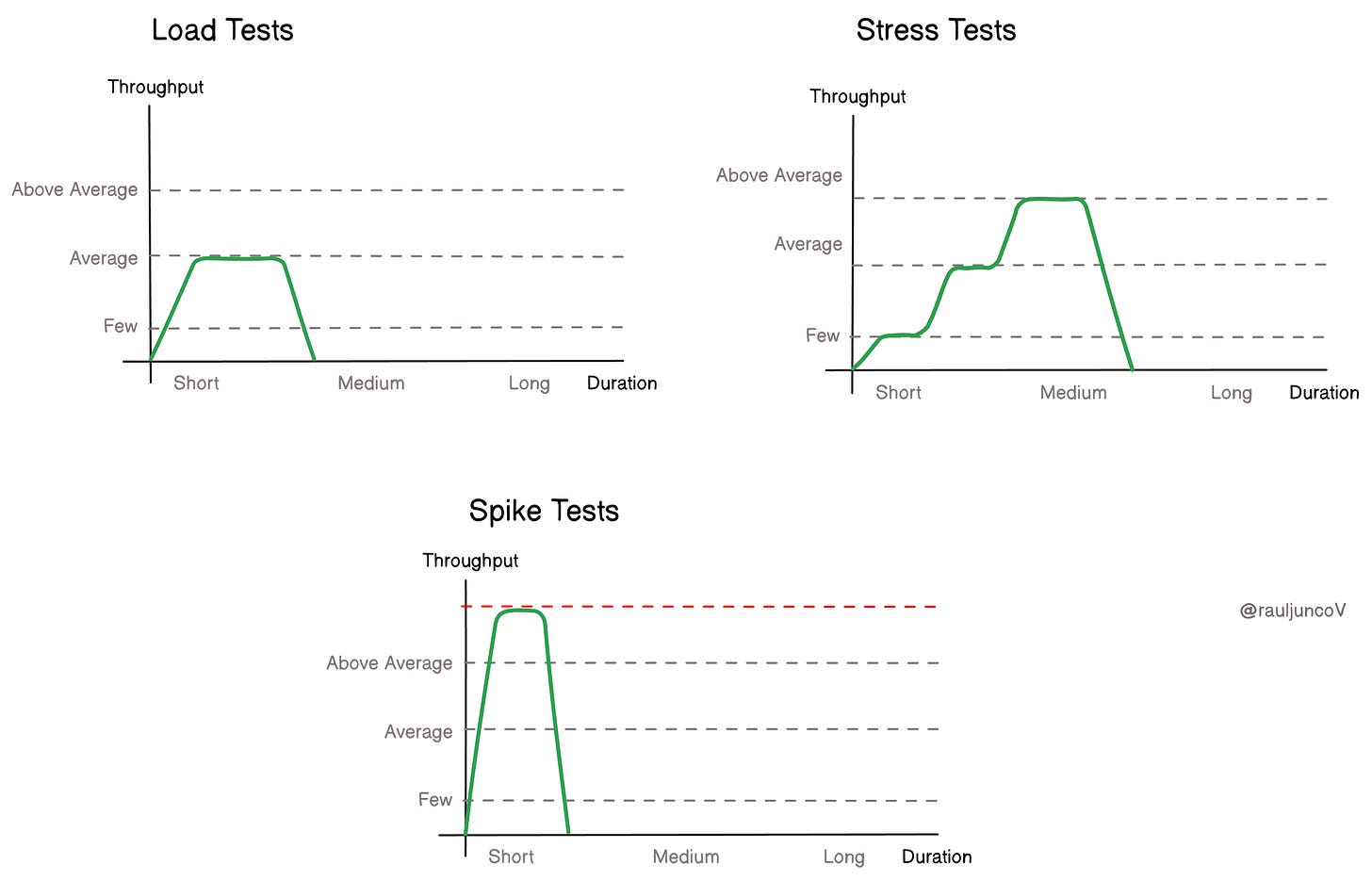

8. Load test peak, not average

By now, I want clear answers:

Can we handle 2× peak?

What fails first?

Do failures degrade or cascade?

Good systems fail partially. Bad systems fall over completely.

9. Document decisions and limits

This is a senior‑level signal.

I document:

What we fixed

What we deliberately didn’t fix

Known limits

Next extraction candidates

System design is not about pretending trade‑offs don’t exist. It’s about making them explicit.

Why this question works so well

This question works because it exposes how engineers think when systems are already under stress.

Strong candidates naturally reason in constraints. They focus on the hot path first, not the entire system. They respect rollout risk and reversibility. And they understand that architecture, by itself, does not equal progress.

In short, it rewards judgment formed by real production experience, not familiarity with trendy patterns.

My Final takeaway

Scaling is not about rewriting systems.

It is about seeing the system clearly under pressure, choosing the smallest levers that create real impact, and reducing blast radius before adding complexity. Most importantly, it is about buying time so better decisions are possible later.

Good system design is not measured by how fast you can draw boxes.

It is measured by how long your system can survive peak traffic without falling apart.

If someone answers this question well, they can built systems that have had to survive peak traffic.

And that’s exactly what System Design interviews are trying to uncover.

Until next time,

— Raul

System Design Classroom is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Spot on, Raul Junco! I would only add - look for any "max count" bottleneck, which very often is your problem under load:

- Max concurrent DB connections settings.

- DB connection pooling settings.

- Max threads limit settings (web servers) - observe request queue being greater than 0.

- TCP stack issues (max outboind TCP connections), especially on Windows web hosting.

I've seen it many times - the server hosting the monolith has a lot of free resources, still the application is frozen! All these arw actually very easy to increase and fix temporarily the issue, to buy time for monoloth decomposition.

Greetings from a fresh subscriber (coming from linkedin) 🙂!